The Warsaw Uprising – a just war?

For this more philosophical guest post I invited my husband, Simon Hanzal, to reflect on the Warsaw Uprising in the context of just war theory. In August 1944, was the unequal fight of the Polish Home Army against the German occupier a warranted decision?

Can war ever be just? If we agree that justice is necessary to any human society, then the question is merely under which conditions war would become just.

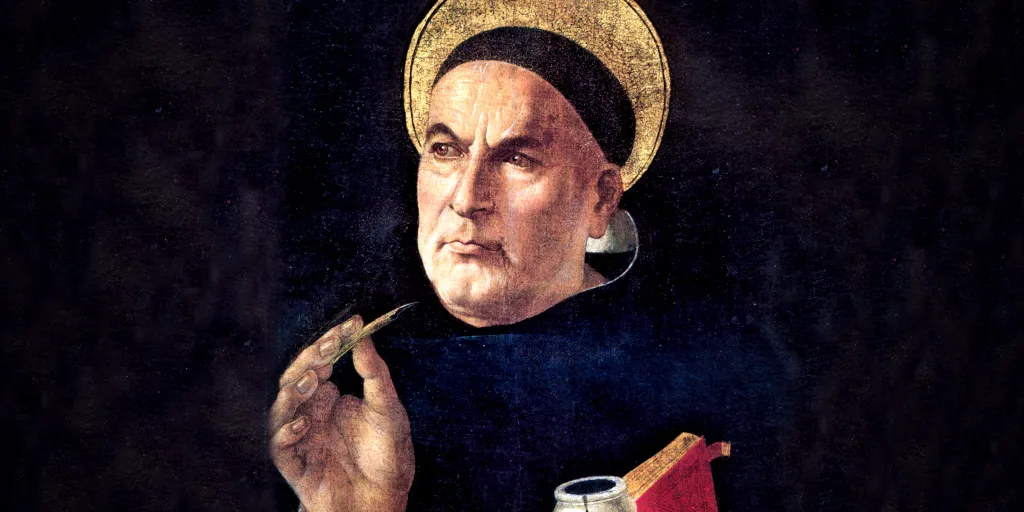

St Thomas Aquinas wisely assembled three necessary conditions for war to be just. Let us have a look at these.

1. Waged with sovereignty

War ought to be waged by command of a sovereign, not an individual. In this way, will of the selfishness of an individual does not lead to redress. Acting on one’s behalf also does not give authority to assemble an army. Leaders wield authority with the condition to guarantee protection of the community that elected them. In fact, it would be unjust for them not to defend those who put trust in them.

Did the Home Army fulfill this condition? Arguably, the main leaders were directly subject to the democratically elected government in exile in London. Therefore, they received mandate to carry out defense of their community.

While some may challenge the continuity and legitimacy of the government in exile, especially after 1945, at the time of the uprising the government was in majority comprised of pre-war leaders.

2. Waged against an enemy who deserves so

Secondly, taking up arms against the enemy can only be done when the enemy deserves so through some fault on their part. St Augustine elaborates that vengeance is fair on an enemy who refuses amends or restoration of that which was unjustly seized.

This condition of just war is most readily accepted in the case of the oppressive Nazi regime in the Second World War. Resistance movements across Europe and in the Third Reich itself bear witness to the universal call to vengeance experienced by Europe’s oppressed communities.

3. Waged with the intention of good

Just acts require the intention of advancing good and avoiding evil. Therefore, acts of cruelty or undue self-enrichment are typically seen as war crimes and forbidden even in times of war.

Oftentimes, war is waged so that peace can be obtained as the chief good. History shows many examples of wars which started as just, but became corrupted. A good example is the Fourth Crusade. What started as a mission of protection of religious pilgrims into Jerusalem turned into a wholly unanticipated sack of Constantinople.

This is the point at which interpretations of the Warsaw Uprising may stumble the most. On the one hand, strong evidence shows that defensive actions of the insurgents would strongly contrast with large-scale war crimes perpetrated by the forces of the occupants. Corruption is unlikely. The uprising lasted two months, far too short to turn into a mission with the potential to inflict unjust harm to the occupant forces.

Consequences of the uprising

In connection with the third condition, there remains the reality of the total destruction of Warsaw and heavy civilian casualties. Along with ethical consequentialism, it may be argued that some of these could be prevented if no uprising took place, or if the insurgent leaders decided to surrender earlier, when victory became impossible. Evidence points to the contrary, as the plans of the enemy for the destruction of the city and genocide of its inhabitants were fully established long prior to the uprising. The only course of action to prevent these to eventually occur was to wage war.

The key factor is the betrayal of the uprising by its Soviet allies. As long as it can be believed that the uprising leaders trusted the Soviets to deliver the aid that made victory possible, the good of peace that they sought was achievable. Crucially, a campaign of disinformation meant that the truth of betrayal was known to the Soviets, but it was kept in secrecy from the uprising leaders.

The only window which can be openly considered unjust was between the discovery of Soviet betrayal and surrender. It is the work of historians to measure its length and assess its nuances. A quick overview seems to suggest that insofar as the events unfolded, the window was very short to none. Not two weeks elapsed since the loss of Powiśle when the betrayal became clear and the insurgents surrendered.

Now, the delay may come down to individual factors, such as exhaustion of the leadership, time needed to fully unveil the Soviet betrayal, administrative confusion and perhaps some deal of disorganisation. In that case the war remained mostly just even in these final weeks. Otherwise, focus of critics should focus on this period.

Politics of burnt ground

Altogether, it is easy to retrospectively judge the uprising by its horrid consequences. The agent of destruction however made no promise that these would not have occurred anyway. Therefore, the destruction may not be seen as a consequence of any uprising and so cannot be ascribed to those who wanted to wage war.

Later events in the second world war show that Nazi politics of burnt ground were applied in other places in Germany. Where escape was frantic in the final days of war, there was no time to destroy. Such is the case of Prague. The local insurgents had no agency in how much the occupiers desired to destroy.

There is only one history. We do not know alternative futures. But principles of just war continue to apply, now more than ever.

Tags:- |

history |

wwii |

warsaw-uprising |